| Published in the January 2001 Issue of Anvil Magazine

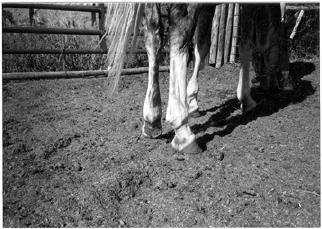

Note: Images with captions are included at the end of this article. "Scratches" is a term that refers to a skin problem on the lower legs of horses, caused by a fungus (and sometimes complicated by bacteria). The affected area becomes crusted, scabby and thickened, creating bumps and sometimes open sores. In severe cases the affected skin may ooze or the whole lower leg may swell, and the horse may become lame. This skin condition generally affects unpigmented skin (the areas of white leg markings) more readily than dark skin, since the unpigmented skin is not as tough-and more apt to chaff and scrape, opening the way for infection. Scratches is a dermatitis, or inflammation of the skin, and the most common cause seems to be the fungus Sporotrichum schenki. Some horses seem to be more susceptible than others, just as some seem more vulnerable to other fungal infections such as ringworm and girth itch. The fungus lives in organic matter and enters through breaks in the skin when the horse walks through contaminated pastures or muddy, swampy areas. The dermatitis that results is basically an inflammation of the deeper layers of the skin, sometimes involving the blood and lymph vessels. The most common site of inflammation is the pastern and fetlock area, often in the heel and back of the pastern where the foot bends. The involved skin becomes warmer, reddish and thickened. Then the skin surface becomes scabby and cracked, and if the condition is not treated it usually becomes badly cracked and oozing and spreads to include larger areas. Infection may also spread to the inner tissues and is sometimes complicated by bacterial infection as well. The thickened skin may come off, leaving bare spots covered with rough skin, or raw areas. Traditional treatments for scratches were astringents like methylene blue, iodine mixed with glycerine, or ointments made with zinc oxide, nitrofurazone and steroids. But a better treatment, recommended by several veterinarians, is a mix of nitrofurazone, DMSO and thiabendazole (a cattle wormer that is also a good fungicide). Thiabendazole cattle wormer paste is hard to find anymore, however (no longer being sold by most veterinarians or mail order livestock supplies because newer drugs have become more popular), so the horsemen can substitute any of the other benzimidazole dewormer drugs, found in horse paste wormers. Some of these are fenbendazole (marketed as Safe-Guard or Panacur), cambendazole, oxybendazole (marketed as Anthelcide EQ), oxfendizole (trade name Benzelmin) and mebendazole. The area on the horse's leg to be treated should first be scrubbed thoroughly to remove all dirt, then the mixture can be applied to the affected part of the leg. The mix should be one part nitrofurazone ointment (an antibiotic salve), one part dewormer paste containing thiabendazole or any of the other benizmidazoles, and one part DMSO. These ingredients can be obtained from a veterinarian. The DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide) helps reduce swelling and inflammation, and also helps the fungicide (the wormer paste's active ingredient) penetrate the area deeply and thoroughly, taking the medication into the underlying tissues. The nitrofurazone combats any bacterial infection that may accompany the condition, and it helps buffer the DMSO so it won't burn or irritate the tissues. The wormer paste kills the fungus. The dewormer is the safest type of fungicide to use in conjunction with DMSO, according to our veterinarian, since it is an oral medication, safe to use internally in the body. Harsh or poisonous fungicides like iodine should never be used with DMSO because the DMSO carries the medication into the body and could cause serious problems. The affected area should be well cleaned before applying the medication, so no dirt or outside contaminants are carried into the deeper tissues by the DMSO. Warm water is usually adequate for washing the leg, and a handy way to apply it is with a well-rinsed dishwashing detergent squeeze bottle, using your fingers to remove any dirt that is clinging to the leg from the ointment applied at the last doctoring session. After the area is washed with warm water and is very clean, it should be dried it with a towel. The skin should not be wet when the mixture is applied. A mix can be made that will be enough for several doctorings, or it can be mixed up fresh each time-just the amount needed for one application. It can be easily stirred up with a finger, in a small wide-mouth jar. If a person doesn't want skin contact with the DMSO, rubber gloves can be used to mix it and to apply it to the leg. Mixed with nitrofurazone ointment, the DMSO doesn't burn or irritate the skin or raw tissues like it can when used by itself, but a person may still "taste" it if your skin comes into contact with it. If using bare fingers to mix or apply the medication, hands should be washed immediately afterward. If applied daily, this mixture usually clears up scratches faster than traditional treatments. Bandaging, even in severe cases, is unnecessary, and can actually be detrimental to fast healing. The moisture should not be held in. With this treatment a bad case of scratches can be cleared up even if the horse must be ridden and continues to get the area wet and dirty when traveling through mud or on a dusty trail. The leg should be washed and medicated each day after the ride. For a really resistant case that has bacterial complications, you can also give the horse oral sulfa tablets to help combat the bacterial infection, and dexamethasone to aid in reducing the swelling and inflammation, according to our veterinarian.

The best prevention for scratches is to keep white-legged horses out of muddy

pastures. The fungus, once introduced into a pasture, remains there indefinitely,

and horses are apt to pick it up when there are cracks or breaks in the skin.

Pink skin chaps, cracks or nicks more easily than tougher, darker skin; that's

why the problem is most common in horses with white leg markings. If a horse

must walk through mud or water often, the skin may tend to chap or crack

more readily, and the fungus may be picked up from the mud. Scratches can

also be a problem in winter pastures, and even dry summer pastures if the

fungus exists in the dust and dirt and is introduced through breaks in the

skin. But if caught early, a few treatments will clear scratches right up.

A more serious, neglected case will take a bit longer.

Return to the January 2001 Table of Contents Return to the Farriers Articles page

|