Published in the October 2000 Issue of Anvil Magazine

The origins of Hopewell Furnace are intertwined with the American Revolution. Most people are familiar with the British efforts before the war to impose taxes on tea coming into America and the resulting Boston Tea Party in 1775. Not so well known, however, are the other attempts by the English government to control American economic life. One of their major thrusts was directed at our iron industry. The British, in the years before the Revolution, passed laws prohibiting American colonists from making any iron products except in the form of rough, cast iron bars. The idea was that these would be shipped to England for refinement into finished products. American ironmasters ignored these regulations, however, and turned out huge amounts of wrought iron products that were commercially competitive. By the 1770s, colonial furnaces, which had great advantages in the form of water power and use of local natural resources, were well established.

It was Clement who operated the furnace during its most productive years. In part, his success was due to luck in timing. By 1816, the systems of transportation were being greatly improved. Congress had finally seen the advantages of protective tariffs. In Pennsylvania and other northern states, slavery was dying or dead. With these and other factors in his favor, Clement was able to turn Hopewell into a major supplier of iron products throughout the new United States. Castings, in particular, proved the key to profit for Clement and, more specifically, it was the popular Hopewell Stove that marked the success of the furnace. For several decades Hopewell Furnace was, in the jargon of the times, an "iron plantation," where entire families worked and lived full time. Blacksmiths, moulders, founders, colliers, clerks, teamsters and many others were all supervised by the ironmaster. The iron ingredients were extracted from the nearby soil. The fuel was made at the site by burning carefully structured piles of wood to produce charcoal. Water-powered machinery gave the force that was necessary to push air into the hearth and raise the temperature of the fires.

The life in Hopewell revolved around yearly cycles. On an annual basis, the furnace would be cleaned. Many of the laborers doubled as farmers during the spring and summer months. For those working around the furnace, the demands could be difficult. Tapping of the furnace was generally done every twelve hours when the furnace was in operation, in order to allow the liquid iron to run off. Every half hour, these laborers (known as "fillers") put around 500 pounds of iron ore into the furnace, along with about 40 pounds of limestone and the appropriate charcoal. Temperatures in the furnace could go up to 3,000 degrees F. The "Golden Years" of Hopewell Furnace were from around 1830 to 1837. In 1837, an economic panic hit the country and resulted in a severe decline in demand for Hopewell Stoves. From the 1840s onward, America was shifting to large-scale concentrations of steam-driven coke and anthracite furnaces. The age of the "iron plantation," where everyone lived and worked in common, was drawing to a close. Clement Brooke retired in 1848 and his successors found that despite a short reprieve during the years of the Civil War, they could not compete against the new integrated iron and Bessemer steel industries. In 1883, Hopewell Furnace closed its doors.

The mansion and the blacksmith shop are only two of the attractions available for visitors to Hopewell today. The old furnace stack is part of the cast house, where the moulders poured the liquid iron into the molds that resulted in creating the stoves and other items. A separate anthracite furnace stands as the mute testimony about one of the last efforts to "modernize" Hopewell in its final active years. Tenant houses, where the families of workers lived, can also be entered. These are small by our modern standards, but clearly were warm and comfortable to the people who used them. Examples of the old charcoal hearths stand close to the cooling shed and the charcoal house. The women did much of the woodcutting that was necessary for the preparation of the charcoal hearths. The company store at Hopewell Furnace is an experience in itself. Old ledgers provide information about employees and their purchasing needs. Several antique stoves are on display along with other diverse items. People made their purchases on credit against their wages. Prices, however, were fair and there was no attempt to cheat or exploit the workers.

At the Visitors Center, several videos are regularly presented, covering such topics as blacksmithing, casting and charcoal making. The details in these are extensive. In the blacksmithing video, for example, the making of a horseshoe is shown from start to finish. A visit to Hopewell Furnace should be a priority to anyone with an interest in American economic or social history. It is a testimony as to how, in an earlier age, the ideas of community and labor were intertwined. The Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site is located on Route 345 North, about ten miles from the Pennsylvania Turnpike interchange at Morgantown. It is open daily including Memorial Day, Independence Day, Labor Day and Columbus Day. On some federal holidays it is closed. For additional information, the phone number is (610) 582 8773. Web site address: www.nps.gov/hofu. The mailing address is: 2 Mark Bird Lane, Elverson, PA. 19520.

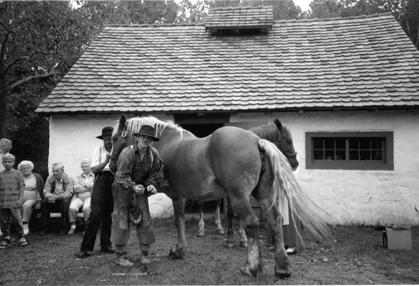

CAPTIONS The water wheel was the central power source for the machinery at Hopewell. This present wheel is a recent restoration. The furnace was an area of constant activity. Workers lived in houses similar to this. Several old Hopewell Stoves, preserved in pristine condition, are on view in the Visitors Center. The anthracite furnace, built late in the history of Hopewell, still stands. Park Ranger Dick Lahey and farrier Darren Quaintance demonstrate the proper techniques for shoeing horses. (photo loaned by Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site) Return to Blacksmithing Articles Page Return to the October 2000 Table of Contents

|

It is easy

to forget that, prior to the Industrial Revolution, labor often had a communal

aspect to it. People lived and worked together in pursuit of common endeavors

that would be done today in factories or by other large-scale mechanization.

This was not only true in farming communities, but also in other kinds of

economic activities, including ironworks. One such "iron plantation" is preserved

as a National Historic Site at the Hopewell Furnace in Berks County,

Pennsylvania.

It is easy

to forget that, prior to the Industrial Revolution, labor often had a communal

aspect to it. People lived and worked together in pursuit of common endeavors

that would be done today in factories or by other large-scale mechanization.

This was not only true in farming communities, but also in other kinds of

economic activities, including ironworks. One such "iron plantation" is preserved

as a National Historic Site at the Hopewell Furnace in Berks County,

Pennsylvania.

Pennsylvania

was especially fortunate in its natural resources. The abundance of raw materials

combined with the availability of water power insured that the state would

be a leader in the commercial life of the nation. In 1771, Mark Bird, a local

businessman, opened Hopewell Furnace in the area known as French Creek Valley

in what is now Berks County, Pennsylvania. One of his earliest products was

stove plates, but such peaceful pursuits did not last long. The opening of

Hopewell coincided with the onset of the American Revolution and, very quickly,

Bird found himself, as ironmaster of the furnace, producing cannon shells

and other supplies for the revolutionary cause. Among the other accomplishments

of Hopewell was the casting of 115 cannons for the American Navy. Bird himself

served as a colonel in the colonial militia and as a Deputy Quartermaster

General. History records that he helped to supply the American troops with

much-needed provisions at Valley Forge. Unfortunately, however, the history

of Hopewell Furnace under Mark Bird is not a perfect one. Bird was the largest

slave owner in the area and at least some of the labor force at Hopewell

under his tenure consisted of slaves. The contribution made by Bird to the

war effort did not bring him great fortune. One of the lesser-known facts

of our struggle for independence is that many Revolutionary War veterans

were never economically helped by the new American government that they had

created. This was the case with Bird. Debts that he had incurred during the

war went unpaid by the federal government. By 1788, Bird had to flee his

creditors and Hopewell was sold at public auction.

Pennsylvania

was especially fortunate in its natural resources. The abundance of raw materials

combined with the availability of water power insured that the state would

be a leader in the commercial life of the nation. In 1771, Mark Bird, a local

businessman, opened Hopewell Furnace in the area known as French Creek Valley

in what is now Berks County, Pennsylvania. One of his earliest products was

stove plates, but such peaceful pursuits did not last long. The opening of

Hopewell coincided with the onset of the American Revolution and, very quickly,

Bird found himself, as ironmaster of the furnace, producing cannon shells

and other supplies for the revolutionary cause. Among the other accomplishments

of Hopewell was the casting of 115 cannons for the American Navy. Bird himself

served as a colonel in the colonial militia and as a Deputy Quartermaster

General. History records that he helped to supply the American troops with

much-needed provisions at Valley Forge. Unfortunately, however, the history

of Hopewell Furnace under Mark Bird is not a perfect one. Bird was the largest

slave owner in the area and at least some of the labor force at Hopewell

under his tenure consisted of slaves. The contribution made by Bird to the

war effort did not bring him great fortune. One of the lesser-known facts

of our struggle for independence is that many Revolutionary War veterans

were never economically helped by the new American government that they had

created. This was the case with Bird. Debts that he had incurred during the

war went unpaid by the federal government. By 1788, Bird had to flee his

creditors and Hopewell was sold at public auction.

The new owners

were equally unsuccessful, however, and the furnace was again sold in 1800.

The third set of owners, Mathew Brooke, Thomas Brooke and Daniel Buckley,

also could not turn a profit and Hopewell was closed in 1808. For a few years,

it remained stagnant. In 1816, Clement Brooke, the son of one of the last

partners, appeared on the scene. From 1816 to 1848, he operated the furnace,

first as resident manager and later as ironmaster.

The new owners

were equally unsuccessful, however, and the furnace was again sold in 1800.

The third set of owners, Mathew Brooke, Thomas Brooke and Daniel Buckley,

also could not turn a profit and Hopewell was closed in 1808. For a few years,

it remained stagnant. In 1816, Clement Brooke, the son of one of the last

partners, appeared on the scene. From 1816 to 1848, he operated the furnace,

first as resident manager and later as ironmaster.

By all accounts,

there was no exploitation of Hopewell workers by management comparable to

the later exploitation of factory workers or miners. The labor force was

generally well paid. Moulders, who did the actual job of casting the iron,

received the highest wages. Other important tasks were handled by the fillers,

who put the raw materials into the furnace, and the guttermen, who controlled

the liquid iron as it flowed from the inside of the furnace. Blacksmiths

also occupied an important position. Horses and wagons needed to be in a

state of constant upkeep and repair. Horseshoes were made by the thousands

to satisfy both the furnace's own needs and for sale to the outside.

By all accounts,

there was no exploitation of Hopewell workers by management comparable to

the later exploitation of factory workers or miners. The labor force was

generally well paid. Moulders, who did the actual job of casting the iron,

received the highest wages. Other important tasks were handled by the fillers,

who put the raw materials into the furnace, and the guttermen, who controlled

the liquid iron as it flowed from the inside of the furnace. Blacksmiths

also occupied an important position. Horses and wagons needed to be in a

state of constant upkeep and repair. Horseshoes were made by the thousands

to satisfy both the furnace's own needs and for sale to the outside.

For a number

of years into the 20th century, Hopewell was in a state of continuous decline.

In 1935, however, the United States government purchased the property and

designated it as a National Historic Site in 1938. Restoration was begun

and the furnace today appears as it did in the 1820-1840 period. Some of

the buildings, such as the ironmaster's mansion and the blacksmith shop,

did not need significant repairs. Others were reconstructed using such

contemporary techniques as wooden joining beams and handmade beams. In many

of the buildings, including the ironmaster's mansion, appropriate antiques

and accessories from the 19th century have been situated for visual effect.

For a number

of years into the 20th century, Hopewell was in a state of continuous decline.

In 1935, however, the United States government purchased the property and

designated it as a National Historic Site in 1938. Restoration was begun

and the furnace today appears as it did in the 1820-1840 period. Some of

the buildings, such as the ironmaster's mansion and the blacksmith shop,

did not need significant repairs. Others were reconstructed using such

contemporary techniques as wooden joining beams and handmade beams. In many

of the buildings, including the ironmaster's mansion, appropriate antiques

and accessories from the 19th century have been situated for visual effect.

In the "old

days" there was a working barn at Hopewell that held between 30 and 40 animals.

These were mainly used for draft purposes. The park rangers today have revived

the idea of live animals at Hopewell and numerous cows, chickens, sheep and

horses now live there, along with a cat.

In the "old

days" there was a working barn at Hopewell that held between 30 and 40 animals.

These were mainly used for draft purposes. The park rangers today have revived

the idea of live animals at Hopewell and numerous cows, chickens, sheep and

horses now live there, along with a cat.