| Published in the January 2001 Issue of Anvil Magazine

Nore: Images with captions are included at the end of this interview. John Rais is Blacksmithing Department Head at Peters Valley Craft Education Center in Layton, New Jersey, located in the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area. Rais got "hooked" on the craft during a welding course for sculptors at Massachusetts College of Art. He received his MFA from Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan. His studio practice includes architectural work, vessels and furniture. Rais has also been developing titanium smithing techniques and, at 26, represents a new generation of blacksmiths, mixing tradition with technological advancements. His metalwork is collected and shown nationally in galleries, museums and magazines.

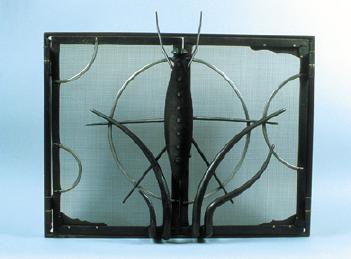

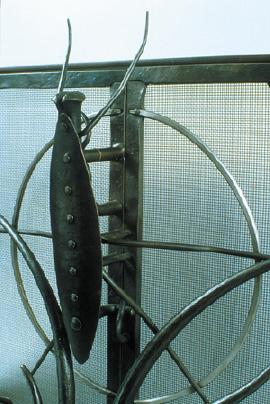

ANVIL: John, where are you from originally? JOHN: I was born and raised in Massachusetts and went to college there. I stayed for about a year and a half after college. I worked at a commercial forge and also at a living history museum as the village blacksmith. All the while I was doing commission work of my own. ANVIL: Did you have your own studio at that point? JOHN: No, but often I used other studios. I used whatever studio I was working in, and usually there was some sort of tradeoff where I was given time to work. ANVIL: Then you moved on to Cranbrook? JOHN: Yes. I went to Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. ANVIL: How did that come about? JOHN: It was actually on a bet with an undergraduate professor of mine who said, "You really need to go there, John. Gary Griffin is an excellent instructor and I think you two would really get along and you would enjoy working with him." I was still considering myself a sculptor at the time and didn't know if I would get in, as I thought it would be a big stretch to go into a metalsmithing program. I did get accepted, however. I figured I would give it one semester to see how it went and after the first semester, I was totally hooked. It's an amazing place. ANVIL: What got you hooked? JOHN: I think what kept me there was the intense intellectual stimulus and the strong community. It was such a friendly group of students with whom I worked there. It's quite a powerful and dynamic place. I learned a great deal just by `soaking' it in. You learn a lot about architecture and three-dimensional design just by being there. ANVIL: And so you did benefit from working with Gary Griffin? JOHN: Absolutely, yes. Gary is a metalsmith and iron worker. One would hardly call him a blacksmith, and I know he probably wouldn't refer to himself as one, either, although he uses some hammering techniques. He uses a lot of specialized fabrication and forming techniques. I worked for Gary part time while I was at the school, helping him with some of his own projects. He is extremely technical and very precise-Gary is quite specific as to what he wants. So there was a bit of a learning curve working for him at first because I had to really understand exactly what he wanted. We would measure tapers with a micrometer, in calipers. There was a lot of precision forging, machining and precision grinding. He really opened my eyes to the world of grinding as a craft. And I firmly believe that it can be a valuable craft technique. He must have had at least 40 different positions in which you can hold an angle grinder in order to get different effects. ANVIL: When did you graduate from Cranbrook? JOHN: In 1998. ANVIL: And you came here to Peters Valley right from there? JOHN: I came here two days after I graduated. While I was at Cranbrook I knew Dan Radven, who was then the resident blacksmith instructor at Peters Valley. After my first year at Cranbrook I was supposed to go back to Boston to work at the living history museum again for the summer and then go back to grad school in the fall. But at the end of that year while I was still working for Gary, Dan called me and said he needed an assistant in the blacksmithing program at Peters Valley for the summer; he asked if I would be interested. I thought about it and told him I would. So I did go, and while I was there as an assistant, Dan decided to leave Peters Valley after that summer, so his position opened up. I didn't think I would qualify because I still had to complete my last year of grad school, but I applied that fall from Michigan and flew back to Peters Valley for an interview. I knew by the end of November that I had the job. I officially signed on here that January while I had one more semester of school. I graduated Friday, May 8, had Saturday, May 9 to pack, and Sunday, May 10 to drive here! I got to the school at midnight, and then worked cleanup duty for two hours because there were such heavy rains in New Jersey that water was coming into the blacksmithing studio. I went to bed at 2:00 a.m., woke up at 8:00 a.m., and started working at Peters Valley. And I haven't left since-it's been two years now. ANVIL: How are things progressing for you here? JOHN: Peters Valley is this wonderful little world in the woods. There is a great deal of intellectual stimulus. There are working professionals and academics teaching workshops and doing their own work, as well. ANVIL: Taking on a position like this at such a young age, do you find that you have to prove yourself to some of the more experienced smiths whom you invite here to teach? JOHN: Even before coming to Peters Valley I had always tried to present myself as a professional. All my schooling-from the undergraduate level on up-trained me to do just that, and so over time, I have grown more confident and comfortable with my position. I think in general that blacksmiths are quite a friendly, accepting and helpful group. ANVIL: What is your favorite thing about Peters Valley? JOHN: I would have to say it's the freedom I am given to represent blacksmithing the way I want it to be represented. That's something I have always had a problem with because I think blacksmithing is still sorely misrepresented. Actually, being underrepresented is probably my biggest concern. I think that being at a place like Peters Valley and doing the programming and gallery shows gives a sense of representation in our field. ANVIL: Through your position here, where would you like to take blacksmithing? JOHN: The broad answer to that would be that I certainly want to see Peters Valley have more visibility for their blacksmithing program. I really want to up the intensity here. I still absolutely love it when I see a beginner come through, even for a five-day course, and become so turned on by blacksmithing that he or she wants to quit their job and become a blacksmith. I've seen it happen. I don't think everyone should do that, but it's great when you see it happen. Specifically, I would like to see more of the apprentice/master format return to Peters Valley. I'm not sure how it can happen, but that's a fantasy of mine. I think that a really good program would be one where students could study with a department head or instructor for an extended period of time, almost like in the professional workplace. They would take on commissions that are high quality and meaningful. The students would work with the master of the project maybe half of the week and then in the classroom for the other half. I think there is such value in learning by working for someone else. And that, of course, depends on the situation of whom you're working for and what kind of work that person is doing. But I think that every up-and- coming smith should do that for some period of time. ANVIL: Do you think you're succeeding in `upping the intensity?' JOHN: I believe it's well on its way, because the students who come into blacksmithing are almost always unanimously excited to be here. ANVIL: Why do you think that is? JOHN: At places like Peters Valley it has that effect, because people are forced to put their lives on hold for a short period of time to be here. It's not like you're taking a night class. They come here and work eight hours in the day and usually at night. They allow themselves the opportunity to remove themselves from their everyday jobs and the rest of their lives for some small period of time, even if it's just for a few days. They get to do something totally different. I think when you allow yourself that type of separation from the rest of your life, it tends to change you in great ways. ANVIL: What is the thing that most draws you to this art form? JOHN: The processes are very direct, because you're with the material the whole way through. Anything that you do to the material requires you to be right there while it's happening. And for me, I've found that the ideas never stop. I haven't had a lack of ideas for iron work-not even once-since I began working with it ten years ago. ANVIL: Currently, what kind of sculpture are you doing? What kind of materials are you using? JOHN: The work I do is becoming split between my architectural work and my vessels. The vessels are basically sculpture. They're much more experimental and I am able to explore with these pieces. They allow me to work out a lot of ideas faster and on my own time. I have a lot of things in metal that I want to see, and the vessels allow me to make those pieces. In a recent artist's statement, I wrote that, in a sense, I make the things I wish I could find. I use a lot of imagery that has a sensibility about it and a form to it, and that looks like something which had been found rather than made. I love the curiosity that found objects have and in my vessels I get to play on that role of the fictitious object. Lately I have been doing fictitious tool forms. ANVIL: Do you name your pieces? JOHN: It really depends on what I want to reveal. I feel funny about titles. I used to wan to do that in the past, but not so much anymore. As soon as you name it something, you lose-or mask-some of the essence of what you were trying to do, just by making the object. By adding the words, you lose some of the mystery. I'm over that now and I do use titles when I feel like I need to use them, but I'm very selective with them. ANVIL: Define what you mean by vessel. JOHN: I'm using the term loosely Some of them are more like bowls and some are baskets. I've been almost misusing the word vessel as the blanket term to cover objects that could or would contain something. These things are marginally functional-they're basically centerpieces. More often than not, people who buy them treat them like a sculpture. For example, a woman bought one of my wall vessels to put letters in- sentimental things. Most of them are not designed to hold liquids. When I was first making them, I was so conscious about having them function. The buyers educated me so that when I would talk to them, I knew that they weren't going to put anything in them and that got me thinking about ancient Chinese pots and other types of vessels that people collect. This brings up the issue of when do I call it sculpture and when do I not. ANVIL: Do you consider yourself to be a sculptor? JOHN: When I send work to galleries they usually will call the work sculpture and I find that interesting-or they will refer to me as a sculptor. And it always makes me chuckle because for a few years, I really wasn't considering myself a sculptor at all. But it's one of those things that is foolish to try to fight. It doesn't really change my work drastically at all so I let people call me what they want, according to how they see me. ANVIL: What would you call yourself? JOHN: Oh, I would just call myself a metalsmith. That's a more general term. Blacksmith is fine, too, but metalsmith suits me better because I do use metals other than iron. That's the term I think more people can understand. ANVIL: Tell us about your architectural work. JOHN: What I've been doing a lot of lately is designing and making fire screens, and I love it; I'm so fascinated by the work. I could do fire screens forever! There is something about the format that I really respond to. They're great because you've got this open space that you have to fill with your creative ideas. It's kind of like just doing a relief sculpture. The amount of function that it has to have is actually fairly low, if you think about the amount of time throughout the year that you're using your fire screen-it's really almost like a wall relief sculpture. It certainly doesn't get daily use; maybe it gets used once a week. That leaves the rest of the week for it to adorn the space. In that respect, it falls under certain criteria that sculpture would fall under, at least most of the week. It has a part-time job, so to speak. I like the interaction that one has, too. When I was making sculpture at school the one thing that was interesting was that it was active, but it wasn't interactive. ANVIL: What do you mean by that? JOHN: The active aspect was that it had a lot of visual energy to it, and that was good. But I think the thing that really interests me with the architectural work is the interaction. It's actually another element of the piece. ANVIL: Meaning that the owner can use it? JOHN: Yes, exactly; the owner interacts with it. He or she actually engages the object and that, to me, is when the object is finished-once you make that initial engagement, such as when you open the door to the fire screen or when you turn on the light within the chandelier. A door handle has a tremendous tactile interaction to it because you're grabbing and turning it. I'm really engaged in the whole premise of use. I also like it because the architectural work does have an historical lineage that I enjoy. Some great examples of iron work throughout history are architectural work. It's a great reference point. It even helps to reference my vessels. When I first began making them, I was dealing with the idea of handles. I started making tool handles because I wanted to imagine or give the reference to some sort of lifting or shoveling or sifting action. ANVIL: Where do you see your work progressing? JOHN: I can see a lot more going on with the vessels. I feel like I have just scratched th surface and I want to keep making them for awhile. I want to make the idea of the vessels turn into more things, and even blend the vessel in with furniture. I've started to do that-in just part of a piece-and then the whole piece becomes furniture. Maybe I'll go into turning the vessels into something that is purely sculpture for sculpture's sake. I think I have a lot more to do in order to expand on the vessels. I have so many ideas with them that I can't even make them fast enough-so, by that rationale, I'll be making them for awhile longer. I want to keep working at combining a lot of the visual language that I've been using with the vessels into the architectural work. I am doing that, but not with every piece; I'd like to combine those two worlds more and more. There is much more that I want to explore in architectural work, also. I want to keep doing fire screens, do more with lighting and I would like to do outdoor seating, as well. That is something that has always interested me. Park benches, chairs-I like that level of interaction, where you actually get to sit on the piece. That's almost like the dry humor of it-you're sitting on a sculpture. That's a phenomenal level of engagement. ANVIL: You've also been working with titanium recently, haven't you? JOHN: Yes, I have. That's becoming a trend in what I've been doing. More often I include titanium with iron work, at this point. ANVIL: How did you become interested in this? JOHN: I got interested in the titanium a number of years ago when a roommate of mine became a bicycle welder at a company that made titanium bicycles. We started talking about titanium and, of course, I was a blacksmith and did a lot of forging, so my first reaction was to inquire about how it forged. ANVIL: Does it forge in the same way as iron? JOHN: There are some differences and some similarities. The general thing with titanium is that you need to watch out for oxidation. It wants to oxidize quickly; it is a very reactive metal. In short, you can get stress cracks and you can fatigue the titanium quickly if you don't protect it from the oxidizing environment. It can't be forge welded under any of the same conditions that iron work can be. I have seen it fused with sterling and other things, but that's an area in titanium where I have only scratched the surface. I think there is so much more experimentation to be done. I find it very enjoyable working with titanium. ANVIL: What do you enjoy about it? JOHN: The alloy that I use is extremely soft when it's hot and extremely hard when it's cold. I love the difference. It is softer than copper when it's hot-and it's just so light. You can design differently with it. I like how it looks with the steel. I put it on a lot of the vessels because I like how it looks-it looks very tinny. You can almost get it to look old or make it look like it can be from any era-present, past or future-depending on the way you treat it. It's a very malleable metal. ANVIL: Is this a trend among other artists? JOHN: It may be. With blacksmiths? I haven't seen too much of it. Maybe in the future it will become a lot more popular. It's almost unavoidable, because it is becoming more accessible. The metals are always dictated by industry and if there is a large amount of it being produced by industry for commercial sale it will be used by blacksmiths, because it will be out there. It is already happening in industry with golf clubs and bicycle parts. Industry says the best thing that ever happened to steel is aluminum, and I would say the best thing that ever happened to aluminum is titanium. I never want to stop working with steel because I love it and there are so many benefits to it, conceptually and technically. But there is no reason you can't use both. ANVIL: What are your feelings about being a young artist delving into new techniques and materials? JOHN: One of my heroes is Edgar Brandt, who is considered to be an art deco iron worker. The thing he loved about iron is that it was the one material that linked art and industry together, and I like that about titanium, too. I wonder what is going to happen with titanium and how that link is going to be formed. I don't want to do reproduction. I want to do the now work. No matter what people try to argue, art reflects industry and technological advancements. In the back of my mind, when I work, I'm always trying to make the work that others would want to make for the next ten years. I don't want to make the work that has already been done. I respect it a great deal and I learned a lot of what I know technically through doing the same work that someone else did 100 years ago or more, but I don't want to do that now. I want to do the work that others would want to do once they saw it. That, I think, is one of the measures of a good work. ANVIL: Thank you, John, for your time.

JOHN: It's been my pleasure.

Peters Valley Craft Education Center is located in rural northwest New Jersey in the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area. Founded in 1970 as a non-profit corporation, the Valley celebrated its 30th anniversary in the year 2000. Originally settled at the turn of the 19th century and formerly known as the town of Bevans, Peters Valley's name is derived from Peter Van Ness, an early landowner and original settler of the area. Today, Peters Valley occupies and administers its buildings in cooperation with the National Park Service. The center houses seven working studios including blacksmithing, ceramics, fibers, fine metals, photography, weaving and woodworking. Each studio is managed by a department head who plans and coordinates the programs. The Summer Workshop Program at Peters Valley offers more than 80 opportunities for beginners up to advanced level students in each of the studio disciplines. Workshops are generally 2 to 13 days in length and begin on Fridays from mid-May through mid-September. Studio assistantships are also available. Assistants learn by working in their chosen field and developing their skills through study and studio projects. Assistants live at Peters Valley and work approximately 35 hours per week. The commitment is a demanding one, but offers the serious student the unique opportunity to explore his or her craft in a supportive community atmosphere. Associate and professional residencies are available as well. Peters Valley, in arrangement with individual colleges or universities, allows credit to be earned at both the undergraduate and graduate levels. It is located at 19 Kuhn Road, Layton NJ 07851. Their phone number is 973/948-5200. Fax: 973/948-0011. E-mail: pv@warwick.net. Web site: www.pvcrafts.org.

|