Published in the Aug - Sept 2002 Issue of Anvil Magazine

Did you ever wonder who "The Village Blacksmith" really was in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's infamous poem? Longfellow's poem was included in the September 2001 issue of Anvil Magazine, but the subject of the poem remained a mystery. It seems that a humble blacksmith from New Britain, CT had captured Longfellow's imagination and endearment. He immortalized Elihu Burritt in prose and poetry. Elihu Burritt was born December 8, 1810 in New Britain, CT to a common, farming family. He was the youngest son of ten children. His father was a Revolutionary War Veteran, a respected shoemaker and farmer, known for his generosity and honesty. His mother was a devout Christian with high ideals and morals. Elihu had the best qualities of both of his parents. His boyhood was difficult. The family had meager means, but he found happiness in reading. The "local library" was the parish church, which had about 200 books. By the age of sixteen, he had read almost every book in his church's library. He enjoyed reading depictions of various ancient wars in the Bible and listening to Revolutionary War veterans recount their old war stories. Elihu had a genuine love for people and for learning.

Elihu didn't have much opportunity for a formal education. His father died

when he was fifteen years old. When he was seventeen, he apprenticed himself

to Samuel Booth, the local blacksmith. He became skilled at his craft, which

went beyond being just a shoer of horses. Elihu wasn't able to attend school

anymore, but continued his studies on his own, while working ten to fourteen

hours a day at the forge. He especially enjoyed mathematics and would imagine

and solve difficult math problems in his mind, while swinging a hammer on

an anvil or pumping the bellows. Elihu Burritt also managed to study Latin,

French and Greek while heating metals or standing over a smelting pot.

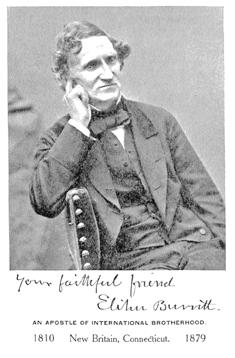

Burritt left New Britain, CT in 1837 and walked to Boston, Massachusetts. He wanted to go to Europe and thought he could find work as a sailor in Boston, but there wasn't a ship sailing out at the time. He decided to stay in Massachusetts and continue his self-education. He then traveled to Worcester, Massachusetts to study at the library of the American Antiquarian Society. The library had a large collection of books, and he was thrilled when given the privilege to use them. He found work at a foundry to support himself and was able to study two hours before breakfast and one hour during lunch. By the time he was thirty, he had taught himself fifty languages. He wanted to use his knowledge to translate books and letters. He wrote a letter to William Lincoln, an acquaintance in Worcester, about helping him find work as a translator and listed his qualifications. Mr. Lincoln was so impressed with Elihu¡s skills that he forwarded the letter to Governor Edward Everett of Massachusetts. The Governor read the letter at a state teacher's meeting and referred to Elihu Burritt as "The Learned Blacksmith." The letter was then printed in a Boston newspaper. After that, Elihu began receiving invitations to lecture throughout New England. Governor Everett introduced Elihu to some wealthy men who had acknowledged him as a scholar. They offered him an opportunity to study at Harvard. Even Henry Wadsworth Longfellow offered to help him with his studies, but Elihu refused their generosity. He wanted to pursue his self-study while continuing his work at the anvil. He loved manual labor and wanted to remain part of the working class. He's been quoted as saying to Longfellow "I shall covet no higher human reward for any attainment I may make in literature or science, than the satisfaction of having stood in the lot of the working man." He believed that hard work was essential to a healthy, happy life. He didn't want to live in the isolated world of scholarly ambition. Worldly successes didn't appeal to him. His quest to attain knowledge wasn't related to his work, but he felt that in addition to the physical rigors of the forge he also had to have intellectual discipline. Elihu wanted strength of mind and body. As he increased in knowledge, his heart grew fonder for his own words. He began searching for his voice and found a way to print his thoughts. He found his purpose in life and became a writer. In his essay entitled "Why I Left the Anvil" he explains why he "dropped his hammer and took up the quill." He moved from his "anvil to the editor's chair." He no longer saw a divine spirit in the sparks. The industrial age was taking over and times were changing, and he didn't think that it was for the better of mankind. While working at his anvil one day, he was suddenly disturbed by a piercing screech. He looked out the door and saw what he called "the great Iron Horse." He called it a beast with a furnace heart, like the great Dragon in Scripture. He was fascinated with technological change, but didn't like some of the results. He was greatly upset about the wars and famines plaguing the country and the world. He realized that more and more resources were going to manufacture weapons rather than more practical items being used in peaceful ways. While working on an essay entitled "Anatomy of the Earth," he had a startling revelation. The essay was supposed to be scientific. He was going to explain how the earth and the human body were related. He said, "rivers, seas, mountains, and soils may be compared with veins, muscles, blood and bones." It then occurred to him that people were created to live together in peace and brotherhood and that all nations and all people were dependent upon each other. He then changed the topic of his lecture to a plea for international peace. This is an excerpt from one of his journal entries dated Wednesday, January 1st 1845 in Worcester: "...I find my mind is setting with all its sympathies toward the subject of Peace. I am persuaded that it is reserved to crown the destiny of America, that she shall be the great peace maker in the brotherhood of nations..." Elihu Burritt became known as "An Apostle of International Brotherhood." He then devoted his entire life to a universal peace keeping mission. He traveled to Europe and organized world peace congresses. He fought to lower ocean postal rates between Europe and the United States. He went to Ireland during the famine of 1847 and pleaded for their cause to help the starving. He spoke out against slavery in America. His writing spoke on behalf of the common man. President Abraham Lincoln appointed Elihu Burritt as Consular Agent for the United States at Birmingham England. Elihu served from 1865 to 1869. This was the happiest time of his life. He returned to New Britain, CT in 1870. In 1872, he was awarded an honorary Master of Arts Degree from Yale. During his last years in New Britain CT, Elihu Burritt became an active citizen of his hometown. He still maintained a literary life, but wrote anonymously and quietly. During the later part of the 19th century, New Britain, CT was a booming industrial city. It became known as the "Hardware City of the World" for its manufacturing capabilities. The city grew from the blacksmithing of small hardware to factory production of machine tools, builder's tools, and ball bearings. Elihu Burritt designed the city seal of New Britain, CT. The seal was adopted by the city council and is still being used today. The seal is an image of a beehive surrounded by "busy bees." The Latin inscription translates to "Industry fills the hive and enjoys the honey." The design was meant to capture the spirit of New Britain's industrial labor force, it's prowess and success. Elihu Burritt died on March 6, 1879. At his death, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow expressed his sorrow for the loss of his dear friend and said, "Nothing ever came from his pen that was not wholesome and good." Elihu Burritt rose from a humble blacksmith to a prominent citizen of the world. Return to the Aug - Sept 2002 Table of Contents Return to the Blacksmithing Articles page

|