| Published in the January 1999 Issue of Anvil Magazine

Please note: The complete version of this interview is located in

our Full Content Area which is available to

Anvil Magazine subscribers and Anvil Online members.

Go to the complete article now

Subscribe

now using our secure server

Note: 12 images with captions are included at the bottom of this

interview.

For the last 22 years, blacksmith Tom Joyce has lived and worked on five

acres with his wife Julie and their two daughters in Santa Fe, New Mexico,

on the same property where he operates his blacksmith shop. He splits his

time between private and public commissions.

ANVIL: Tom, why did you choose Santa Fe as a place to live?

TOM: My mother moved to El Rito, a town north of Santa Fe, when I was 12.

During summer visits with her after my folks divorced, I knew I’d like

to live in New Mexico at some point. She moved down to Santa Fe in 1974.

In 1977 I asked her if I could fix up the chicken shed in her backyard and

make it a place to live and work. I set up my first blacksmith shop in one

of the rooms which I added to the original structure.

ANVIL: And so that was your first shop?

TOM: Not exactly. During my summers in El Rito, I worked in the shop of a

printer, helping him set type and doing other odd jobs for him. His machinery

was constantly in need of repair and he had set up a forge just to keep on

top of those repairs and to provide agricultural tools for the village farmers.

I was included in all that work, as well. During the day I helped him in

the print shop and in the evening I worked at the forge. When I was 16, he

decided to move the printing shop to Albuquerque, about 125 miles south of

El Rito. He didn’t want to let go of his place in El Rito, his home

and blacksmith shop, so he offered me the place, including the forging shop,

for $27 a month rent. I was 16 then....

<End of Abstract>

Please note: The complete version of this interview is located in

our Full Content Area which is available to

Anvil Magazine subscribers and Anvil Online members.

Go to the complete article now

Subscribe

now using our secure server

Look for Part II in next month’s issue.

Photos by Tom Joyce

1. Double spiral compressed bowl. Forged iron, 2.5”h x 17.75”w

x 14”d. |

|

2. Double spiral compressed bowl, detail.

To make this piece, an 8” wide and 55” long strip of iron is rolled

into a full-bodied circular figure; in this case, a double spiral. By forging

it flat while hot, an almost two-dimensional straight line geometric figure

emerges. The top subtly reveals, through textural differences in the layers,

a ghost-like image of what can’t be seen on the underside. The mating

surfaces disclose a visual record of each onto the face of the other; thus,

the top shares the bottom with the viewers as the bottom shares the top. |

|

| 3. Room divider, two sections/three. Forged iron, 60”h x 220”w

x 16”d. Photo by Nick Merrick.

The room dividers are patterned after the autumn seedhead of a local ground

cover called gramma grass. The arcing lines of the dividers reflect curves

in the home’s floor plan. Though separated by a series of massive columns,

the forged elements stretch visually beyond their frame to create movement

among the parts. To make the arcs, the flat, tapered forgings are fullered

and folded to produce an angled web. To curve the bar, I concentrated my

hammer blows along one edge of the steel webs, thereby lengthening the edge

and forcing the steel to curl. At the same time, the hammer imparts a distinct

texture that suggests a seed-like surface. |

|

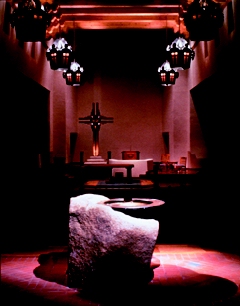

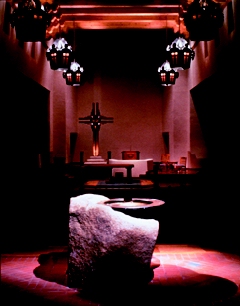

| 4. Baptismal font, Santa Maria de la Paz Catholic Community, Santa Fe,

New Mexico. Forged iron, bronze, granite. 42”h x 72”w x 40”d. |

|

| 5. Baptismal font, detail. Photos by Nick Merrick.

The wide, circular ledge surrounding the bronze font was forged from objects

donated by parishioners of the Santa Maria de la Paz Catholic community in

Santa Fe. Each object represents an important memory from the individual’s

past: garden fencing from a deceased grandmother’s garden plot, an old

key found by a nun on pilgrimage in Nazareth, Israel, 25 years ago when she

was deciding whether to enter the convent, hardware which was the only remaining

evidence of a family home destroyed in a fire, a Nash Metropolitan car jack

from the last car the parish priest owned before entering the seminary. These,

along with many other fragments of donated iron, were combined to illustrate

a multi-layered historical matrix. The children are baptized in the living

memory of their ancestral roots as they are welcomed into the church.

The sound of water resonates throughout the church as it runs continuously

out of the font and over the granite boulder that holds it. Oxidation from

the font and minerals in the water mark the passage of time on the stone

surface. No synthetic finish was used on the piece, so parishioners share

in the maintenance of it through daily oiling. This activity further engages

each person, reminding them of the sacrament central to this vessel and the

life-giving importance of the water it contains. |

|

| 6. Hammer. Cameroon, Africa. Iron, 16.25”h x 3.5”w x 3.5”d.

From the collection of Tom Joyce. |

|

| 7. Bellows. Songye - The Democratic Republic of the Congo. Wood,

24.25”h x 13.25”w x 3.5”d. From the collection of Joel Cooner.

African bellows, constructed from carved wood or sculpted clay, consists

of two bowl-like chambers covered with a bag of animal skin. The skin envelops

a volume of air which, when compressed, is forced out through a tubular passage

to fan the fire. Many African cultures view the manufacture of iron as a

procreative process whereby the union of primal elements — earth, air,

fire and water — conceives iron as its offspring. The sexual metaphor

is illustrated through the bellows, carved in phallic form, that rhythmically

pumps air into the furnace or forge. |

|

| 8. Courtyard gates in progress. Tom Joyce heating tenons to join up the

gate frame. |

|

| 9. Courtyard gates. Forged iron, rust patina. 90”h x 72”w x

6”d. |

|

| 10. Courtyard gates, detail. Photos by Tom Joyce. |

|

| 11. Hoe Currency. Idoma, Nigeria. Iron, 31.5”h x 11”w x

0.375”d (average dimension). From the collection of Tom Joyce. |

|

| 12. Chieftain’s short sword, bango bwagogambanza. Lobala/Ngbaka/Nzombo

- The Democratic Republic of the Congo. Iron, wood, 19.75”h x 6.75”w

x 1.5”d. From the collection of Tom Joyce. Photos by Tom Joyce.

The design of this blade, based on human form, evolved as a variant of blades

initially reserved for ritual executions. |

|

|